When I finally realized my gender identity around my junior year of college, one of the first things I did was attend a meeting of the women’s group on campus. It did not go as planned.

It was not my first encounter with feminism. I had been taught about women’s liberation all my life. I was raised by a strongly feminist mother who told me horror stories of being required to wear skirts as a child, and who encouraged me to become whatever I wanted, regardless of gender stereotypes. In the house where I grew up, Barbies were unwelcome, and Our Bodies, Ourselves was prominently featured on the bookshelf. Yet in spite — or perhaps because — of these early lessons, I never really identified myself as a feminist. To my younger self, my mother’s feminism seemed historical; I had never been prevented from doing or saying something because of my X chromosomes, so I assumed that the need for action had passed.

As I grew into young adulthood and became more aware of the world around me, those assumptions vanished. I learned about women’s struggles abroad, and also those closer to home — and the more I learned, the more I realized that I was also struggling. I began to recognize and interrogate the gender roles I’d been brought up with, not because my parents had fed them to me, but because I had absorbed them from the larger culture. From fairy tales and movies, textbooks and TV shows, toy aisles and playgrounds, I had picked up the stereotypes to which I had earnestly striven to conform. In those first years of college I realized, with the sudden shock of a cold-water wake-up call, that I didn’t want to wear skirts and make-up and date boys. I had only assumed that I did.

It took more of a push for me to recognize my transgender identity (which is a story for another time) but when I came back to college in the fall of my junior year, I felt electrified by my new knowledge. Ironically, it was the realization that I am not a woman that made feminism and gender studies feel relevant and personal to me. It was in the midst of this giddy excitement that I went along to that women’s group meeting on campus, but I was about to get a shock of a different kind.

I can’t remember the name of the club, nor the discussion topic for that day. I do remember that most of the other group members were also residents of the Womyn’s House on campus, an all-female dorm for students who were devoted to feminist causes. The discussion, from what I recall, was avid and fruitful. It was towards the end of the meeting that I had the opportunity to introduce myself, and it was one of the first places where I shared my transgender identity with others — and the first where I shared it with strangers.

I don’t know what I expected — support, solidarity, encouragement? — but it wasn’t what I got. It could have been worse; I could have been yelled at or ridiculed, or even subjected to violence, as so many transgender people have been. Instead, what I encountered was a sudden distance, with a hint of betrayal.

The women at the club that night didn’t see me as a fellow feminist warrior. They saw a tool of the patriarchy. Why do you want to be a man? they asked me, as if I had just announced to a group of socialists my intention to become a hedge fund manager. Why aren’t you happy being a woman? What’s wrong with women? Why do you want to switch sides? Not everyone said these things, but the ones who did are the ones I remember. To them, I wasn’t a gender pioneer. I was a traitor.

I never went back to the women’s issues club. I still believed in all of the things they wanted to achieve — equal rights, equal pay, respect for women and their bodies — but I didn’t feel comfortable in that group. For a long time after that encounter, I even stopped calling myself a “feminist,” advocating for words like “humanist” or “equalist” instead.

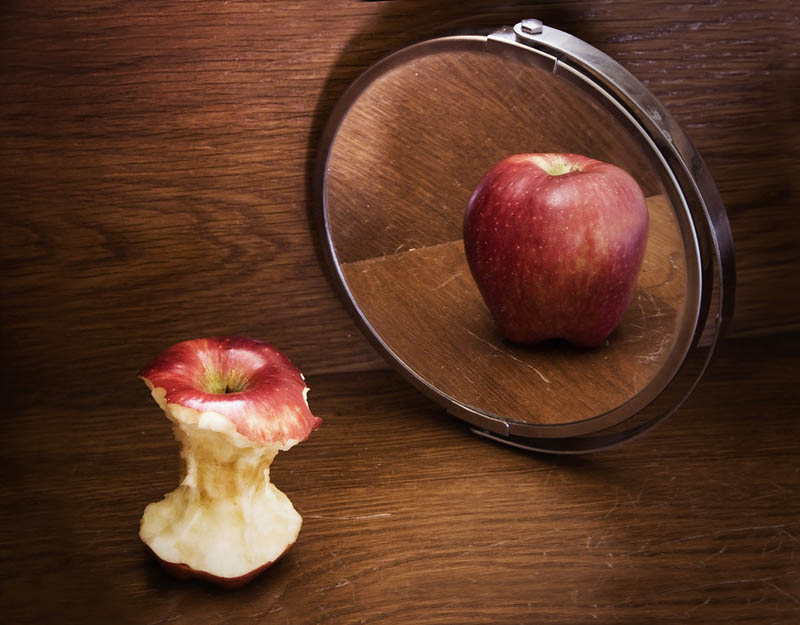

I still consider myself a humanist, but now, more than ten years after that club meeting, I am beginning to reclaim my feminism. For a long time I thought that “feminism” had an image problem, that the word was too scary or too exclusive or too damaged by its enemies to remain relevant. Now I know better, thanks to another word with an image problem: “queer.”

My understanding of the word “queer” has always been a positive one, associated with things like queer studies, queer theory, genderqueer, and the LGBTQ community. But when I was researching the etymology of the word for a presentation earlier this year, I realized how profoundly its meaning and usage have changed in just my own lifetime. If a former slur can become the name of a movement, then surely we can’t give up on the name of the movement that came before it.

The feminist movement laid the groundwork for the gay rights movement, and both still have work to do. So I’ve put the past behind me to say:

I am a feminist.

And so can you.