Reclaiming My Feminism

/0 Comments/by Aiden James KoscieszaWhen I finally realized my gender identity around my junior year of college, one of the first things I did was attend a meeting of the women’s group on campus. It did not go as planned.

It was not my first encounter with feminism. I had been taught about women’s liberation all my life. I was raised by a strongly feminist mother who told me horror stories of being required to wear skirts as a child, and who encouraged me to become whatever I wanted, regardless of gender stereotypes. In the house where I grew up, Barbies were unwelcome, and Our Bodies, Ourselves was prominently featured on the bookshelf. Yet in spite — or perhaps because — of these early lessons, I never really identified myself as a feminist. To my younger self, my mother’s feminism seemed historical; I had never been prevented from doing or saying something because of my X chromosomes, so I assumed that the need for action had passed.

As I grew into young adulthood and became more aware of the world around me, those assumptions vanished. I learned about women’s struggles abroad, and also those closer to home — and the more I learned, the more I realized that I was also struggling. I began to recognize and interrogate the gender roles I’d been brought up with, not because my parents had fed them to me, but because I had absorbed them from the larger culture. From fairy tales and movies, textbooks and TV shows, toy aisles and playgrounds, I had picked up the stereotypes to which I had earnestly striven to conform. In those first years of college I realized, with the sudden shock of a cold-water wake-up call, that I didn’t want to wear skirts and make-up and date boys. I had only assumed that I did.

It took more of a push for me to recognize my transgender identity (which is a story for another time) but when I came back to college in the fall of my junior year, I felt electrified by my new knowledge. Ironically, it was the realization that I am not a woman that made feminism and gender studies feel relevant and personal to me. It was in the midst of this giddy excitement that I went along to that women’s group meeting on campus, but I was about to get a shock of a different kind.

I can’t remember the name of the club, nor the discussion topic for that day. I do remember that most of the other group members were also residents of the Womyn’s House on campus, an all-female dorm for students who were devoted to feminist causes. The discussion, from what I recall, was avid and fruitful. It was towards the end of the meeting that I had the opportunity to introduce myself, and it was one of the first places where I shared my transgender identity with others — and the first where I shared it with strangers.

I don’t know what I expected — support, solidarity, encouragement? — but it wasn’t what I got. It could have been worse; I could have been yelled at or ridiculed, or even subjected to violence, as so many transgender people have been. Instead, what I encountered was a sudden distance, with a hint of betrayal.

The women at the club that night didn’t see me as a fellow feminist warrior. They saw a tool of the patriarchy. Why do you want to be a man? they asked me, as if I had just announced to a group of socialists my intention to become a hedge fund manager. Why aren’t you happy being a woman? What’s wrong with women? Why do you want to switch sides? Not everyone said these things, but the ones who did are the ones I remember. To them, I wasn’t a gender pioneer. I was a traitor.

I never went back to the women’s issues club. I still believed in all of the things they wanted to achieve — equal rights, equal pay, respect for women and their bodies — but I didn’t feel comfortable in that group. For a long time after that encounter, I even stopped calling myself a “feminist,” advocating for words like “humanist” or “equalist” instead.

I still consider myself a humanist, but now, more than ten years after that club meeting, I am beginning to reclaim my feminism. For a long time I thought that “feminism” had an image problem, that the word was too scary or too exclusive or too damaged by its enemies to remain relevant. Now I know better, thanks to another word with an image problem: “queer.”

My understanding of the word “queer” has always been a positive one, associated with things like queer studies, queer theory, genderqueer, and the LGBTQ community. But when I was researching the etymology of the word for a presentation earlier this year, I realized how profoundly its meaning and usage have changed in just my own lifetime. If a former slur can become the name of a movement, then surely we can’t give up on the name of the movement that came before it.

The feminist movement laid the groundwork for the gay rights movement, and both still have work to do. So I’ve put the past behind me to say:

I am a feminist.

And so can you.

Body Image and the Transgender Man

/0 Comments/by Aiden James KoscieszaThere has never been a time in my life when I did not feel fat.

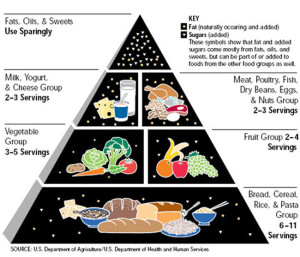

I was never directly bullied for my weight when I was a kid, but I was always aware of it. There was an undercurrent of worry to my mother’s persistent efforts to teach me about nutrition. I remember having colored cards that represented servings on the now-obsolete Food Pyramid, which I would move from one envelope to another as I “spent” them throughout the day. I was required to join one sport or physical activity per season, a melange that included a lot of left-field daydreaming (few balls ever sailed that far), soccer goalkeeping (I didn’t have to run much, and had the advantage of surface area when the ball came at me), and one ballet performance where I was cast as “the boat,” a part where my body was literally covered by a cardboard set piece as I danced across the back of the stage.

My favorite activities were ice skating, because it required big puffy winter clothes, and swimming, where my body was hidden by water and my buoyancy was an asset. Although I thought of myself as anti-sport and proudly self-identified as a nerd, in retrospect I did and enjoyed a lot of athletic activities as a child. My elementary school summers were spent hiking in the mountains or swimming in the rivers of Vermont, where I grew up, and the winters were filled with cross-country skiing, skating over frozen lakes, and trekking through snow-covered forests. Yet even when I passed the swimming test and got my first job as a YMCA lifeguard at 15, I was never thin. And I knew it.

What started as an uncomfortable but accepted childhood reality — one friend nicknamed me “chipmunk” because my cheeks were fat — grew into a filter of shame that overlaid my self-image. As the new kid in middle school, having just moved south to Pennsylvania and away from my New England roots, I took to wearing huge, oversized T-shirts over leggings, a combination that was well out of fashion but which concealed my lumpy body from sixth-grade eyes.

My new hyper-awareness of body image coincided with the advent of puberty. The shock and dismay that I would later recognize as dysphoria stemming from my trans* identity was immediately mixed up with body shame. In retrospect, that body shame might have been the reason why I didn’t understand my gender identity until much later, when I was halfway through college: I knew that my body felt wrong and awful, but rather than realizing that it was because I was a man growing unwanted breasts, I assumed that it was because I was fat and ugly.

Transition has helped me to make incredible progress towards a positive body image. Part of this is due to physical body changes, like hair growth and fat redistribution, that stem from hormone treatment. Part is simply the relief that comes with aligning my physical body with my gender identity — I recognize myself when I look in the mirror, rather than staring at a stranger. Another part is the shift in expectations that comes with a new set of gender norms: where I was previously seen as a stocky, broad-shouldered, big-footed girl, I’m now a medium- to slim-built man. My clothes are sized small or medium instead of large to extra-large. As transparently artificial as that barometer is, it still makes me feel better.

Yet even as a confident, self-assured, outspoken adult, I still struggle with my body and weight, and I think a lot of that stems from being raised as a girl. Our society glamorizes Photoshopped supermodels and bombards women with unrealistic body images and product advertisements that play on shame and self-hatred, and it’s hard to shake off those messages. The ideal that I imagine for myself is not a hunky, muscular, square-jawed movie star but a slim, slight-shouldered, and slightly androgynous masculinity that has more in common with British alternative rock than, say, pro wrestling. Is this because I accept a wider spectrum of masculinities, or because I was bombarded throughout my childhood with the message that big is not beautiful? It’s hard to say.

What worries me is that I, at thirty-one, am staring at the mirror and yearning for the flat stomach of rock stars and fashion models. Even after transition, after rejecting the expectations that came pre-packaged with my assigned sex, after taking control of my own gender identity and exercising my agency to live as my authentic self, I still dream of being skinny.

If my female upbringing is still warping my body image two decades later, what does that mean for today’s fifteen-year-old girls?

Transgender Day of Visibility and Being “Out”

/0 Comments/by Aiden James KoscieszaToday is the sixth annual International Transgender Day of Visibility. The holiday, started in 2009 by Rachel Crandall of Transgender Michigan, acts as a happier counterpoint to the sobering Transgender Day of Remembrance, which mourns the lives that we have lost. TDoV is a celebration of trans* identities and an opportunity for trans* people to be open, to be proud, and of course, to be visible to the world around us.

Visibility is at the core of my speaking work, yet it has been a struggle in my own life. I think this is true of most trans* people. Some of us have too much visibility. We even have a term for it in our own vernacular: being “clocked” means being noticed or called out as transgender when one is trying to blend in. For trans* people who are trying to fly under the radar (note that I don’t say “pass” — I’ll explain why I hate that term in a later entry), visibility can lead to discomfort, fear, or even violence. Trans women, particularly trans women of color, are especially vulnerable to hate crimes — put simply, for some trans people, visibility can be dangerous.

My struggle is with the opposite end of the spectrum: a lack of visibility. Broadly speaking, trans people are often invisible to the world at large. In 2015, most Americans know someone who is gay, or can at least name a gay celebrity; although trans celebrities like Laverne Cox and Janet Mock have seen a flurry of attention in the past year, many people are not yet familiar with trans folks in their personal lives. Politically speaking, this is a challenge. The saying goes “you can’t hate someone whose story you know” — meaning that once we form a personal connection with people who are different from ourselves, it’s easier to understand and accept them. The opposite, sadly, is also true: it’s easy to hate (or fear) people you don’t know.

What this means for trans folks is that if people don’t know about us, it’s hard for them to empathize with us, or to resist the media caricatures of transgender people. This is why TDoV is so important for our community: the more people we can reach and connect with, the better our chances of gaining legal protection from discrimination and violence, which we sorely need.

But visibility also has a more personal side. Like most trans people who tend to be read as cisgender, I struggle with the question of when to disclose my gender identity. I don’t consider this “coming out,” because I have never been “in” — from the time I first discovered my gender identity, I have been very open and honest about it. The existence of this website means that my gender and history will never really be a secret, and I celebrate that. However, most people don’t Google me the minute we meet, so there are plenty of people in both my personal and professional life who simply don’t know that I’m trans. It’s not that I’ve kept it from them. It just hasn’t come up.

So when, if ever, do I tell people that I am transgender? My general policy is to be myself and carry on conversations without self-censorship. If something I say or do confuses someone, I’ll explain my gender identity; if it doesn’t come up, it probably isn’t relevant to the discussion. But what about days like today, when I want to speak up and identify myself even outside of a trans-related conversation?

In honor of Transgender Day of Visibility, today I started both of my classes by telling the students about my transgender identity. I gave them a brief introduction, then disclosed that I am trans and encouraged them to seek out articles or other media about trans* people, and to ask me questions if they are curious. I was met with a warm, positive, and curious response — a perfect TDoV outcome. I hope that all of my trans* and cis friends — and everyone reading this — will take a moment today to learn about trans* people, and share that moment with someone else. Spread knowledge, and stamp out hate — and let’s keep TDoV going all year long.